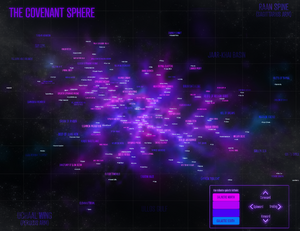

Covenant Sphere

From Halo: Daybreak

| This article is currently under construction. As the subject is under active development, information here may not yet be final. |

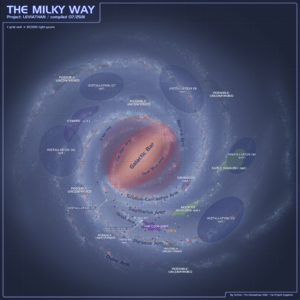

The Covenant Sphere encompasses the Covenant's territorial holdings in the Milky Way galaxy. The Covenant's religious and cultural sphere of influence is often more specifically referred to as the Holy Ecumene. Though their empire was primarily based within the galaxy's Orion Arm, known to the Covenant as the Raan-Uchaal Bridge, the Covenant conducted expeditions further out into the greater galaxy with relative frequency, and had remote holdings and listening posts as far as the neighboring spiral arms. Still, the sheer size and number of stars in the galaxy meant that the Covenant's knowledge on the overall galaxy beyond the Orion Arm and its immediate neighborhood remained limited to those expeditions and outposts, and as time passed even they passed out of memory if they did not yield major discoveries. The hub worlds of the Covenant Sphere were linked together by the vast collection of slipspace passageways known as the Arterial Network. These focal worlds were the Covenant's primary centers of commerce, military power and industry outside High Charity, and acted as both the capitals of the Covenant's provincial domains and nodes for regional expansion and exploration.

The average Covenant citizen is only aware of the breadth of the entire Holy Ecumene in the most abstract sense. Hundreds of billions live and die without ever setting foot on another world, and it is mostly traders, explorers, higher nobles and those serving on the Covenant's fleets that have the privilege of exploring faraway reaches of space. Not only did each clan, population and world have their own traditions, histories and cultural differences, but so did each cluster of civilization. People on one end of the empire were largely unaware of what went on in the other side, aside from tales carried by spacers, warriors and other wanderers. Many expansion regions were effectively islands, connected to the Covenant at large only via the grand wavecasters accessible only to their highest leadership.

A large portion of the Covenant (including its holy city, High Charity) was also migratory, endlessly traveling throughout the Holy Ecumene and even uncharted regions in large armadas and massive worldships. These populations are known as Peripates, and formed a category of Covenant subjects distinct from the planet-based "Placid" societies.

Covenant expansion[edit | edit source]

Covenant expansion trends were driven by three major factors: slipspace routes, the presence of natural resources, and the search for Forerunner relics. Resource scarcity was at times a problem, due to strip-mining by prior civilizations, and there were entire regions of space the Covenant effectively bypassed due to their paucity of natural resources. Islands of civilization clustered around the most efficient slipspace routes where it was most lucrative to transport enormous amounts of goods back and forth. Finally, Forerunner relics were always the primary driver of settlement and discovery, and many a reliquary would eventually become a key hub world in its own right.

The Covenant had long ago reached the point where its expansion front wasn't a single expanding bubble but a vast collection of islands, each of them launching their own outward explorations in their respective neighborhoods. Expansion was centrally controlled from High Charity, but depending on the age, considerable responsibility was also laid on local lords and magistrates to carry out the High Council's mandates. In the most important cases, those usually being strategically important reliquary-worlds, High Charity itself would spearhead and oversee their colonization and settlement, sometimes spending entire ages gracing a budding holy world and nourishing its early development with a steady stream of wealth, technology and the most capable personnel in the Covenant.

Otherwise, wealthy clans might raise their own settlement-fleets, a practice most favored in the Covenant's most recent peak of feudal power around a millennium ago, and before that, in the Covenant's first centuries. A clan's ability to muster their own exploration and colonization missions was seen as a sign of power and prestige, and establishing holdings and outposts in outlying systems - or better yet, bringing back holy relics - could be a surefire way to advance along the ladder of Covenant aristocracy, as well as attaining tithing remissions. In regions with wealthy and strongly-led clans, the practice could yield bountiful results, but where the aristocrats were quarrelsome, poor or otherwise struggling, it could lead to cycles of stagnation lasting ages, sometimes affecting the traffic flows across the entire Covenant. Most recently, this distributed colonization model has fallen to the wayside with the centralization of functions to Ministerial exploration fleets, which has been one of the many grievances of the regional aristocracy over several ages. Advances in communications and travel speeds over the last millennium had enabled the Covenant to effectively centralize many functions formerly delegated to the aristocracy, which was often if not always beneficial to the Covenant at large, but eroded the nobles' firmly entrenched power base and limited the established mechanisms of advancement within their ranks. This issue of centralization was one of the burning political questions that divided not only the Sangheili and the Prophets, but also the Sangheili themselves, as there remains a growing faction that sees the predominant system of nobility as not only outdated, but also recognize it as being grossly bloated - the use of the client races for most manual labor had made it easier for Sangheili to advance to and within the aristocracy even in peacetime, which left the Covenant with a severely inflated Sangheili noble class.

In the Covenant's first millennium, expansion was even less centralized, with then-remote colonies hardly having any contact with one another. In those times worlds would be ruled by Sangheili warlord-kings in an early version of what would become the Covenant's latter-day feudal arrangement; this was originally meant to make a distributed empire easier to govern while keeping the Sangheili happy, but in the absence of effective communication networks, it too often resulted in major internal fracturing both culturally and politically, and a wave of bloody civil wars between the warlord-kings ended that era.

High Charity was also not the Covenant's only mobile base station, though it was by far the largest and most resplendent, and there were many lesser support-platforms, ark-vessels or seed-ships, blazing trails to faraway stars; some of these may still continue their missions deep beyond the Covenant's fringes, oblivious to (or choosing to ignore) the developments of the Great Schism. Oftentimes a world's primary orbital spaceport or primary settlement may have its beginnings in the seed-ship that had originally given rise to the colony. Very often, conventional armadas and their support platforms (such as the Unyielding Hierophant) would double as colony ships, both transporting colonists and their infrastructure as well as safeguarding them from pirates, raiders and the rogue factions that existed in the Covenant's peripheries.

For settlement efforts, the presence of habitable or habiformable worlds was preferred, but not mandatory, as space habitats could be constructed instead; while many Covenant - specifically Sangheili - do prefer living on natural planets, there are entire subfactions and groups of the Covenant well-accustomed to space habitation. Many Kig-Yar in particular, already used to space living in their home system and deeming gravity wells an unnecessary hindrance, would settle in either orbital stations or asteroid belts that wealthier Sangheili clans deemed beneath them. The Covenant rarely habiform worlds unless one is deemed strategically significant enough for the process, and many Sangheili cultural traditions actually prefer to leave inhabited worlds as untouched as possible; when necessary, terraforming should be carried out with a deft touch.

Marches[edit | edit source]

In theory, the Covenant claimed dominion over the entire galaxy. In practice, the boundaries of the Holy Ecumene were broadly delineated by what are known as the marches. The Covenant Empire did not have a clear, physical border, which would be impossible to enforce in space. Rather, it had wide, sweeping frontiers of space where Covenant civilization thinned out and gradually gave way to wild space. While there is no agreed-upon definition on where the march exactly "ended" (because it effectively did not), in effect the marches could well be over a thousand cubic light-years in volume.

Because of their diffuse nature, the marches were rarely empty of civilization altogether, even as the reach of the Covenant metaculture there was tenuous. Within and beyond the marches existed various Covenant offshoots and splinter-societies with no effective ties to High Charity, the most notable of these being the Peripherals and the Outliers. Notably, this distinction is sometimes a debatable one. Peripherals were generally small groups, often encompassing only one world and separated from High Charity by time and distance, if not loyalties, and usually maintained a tenuous link to the Covenant superculture and bureaucracy. Meanwhile, Outliers were entirely cut off, often if not always on purpose, with them having deliberately fled Covenant space for religious, ideological or cultural reasons and seeking to establish a new social order to replace that of the Covenant. These offshoot civilizations were known as the Strays or the Strayed, and when contact with the Covenant collective resumed, what ensued was generally bloody warfare and eventual reassimilation (in some cases extermination) of the Strayed culture. However, the total number of currently-active Outlier or Stray civilizations can only be guessed at. Minor species operating within the marches and even further inside the Holy Ecumene but not fully assimilated to the Covenant were known as the Fringe. Peer civilizations, or outside civilizations the Covenant did not exert any form of control over, were known as the Ulteria.

As the Covenant expanded, so too did Covenant presence in the marches, and the reach of Covenant outposts and bastions there. One day, marches were destined to become civilized and trafficked heartlands of the Covenant Empire, but this might take centuries, even millennia. One factor that accelerated this development was the growth of marcher base-worlds into full-fledged hubs or focal worlds. As base-worlds became more established, they diversified in their exports and became full-fledged colonies in their own right. This in turn attracted commerce, and the charting of superior slipspace routes. And one day, what had once been a humble bastion world had become linked to the vast Arterial Network of the Holy Ecumene, like a new node in a neural network that ever strove for greater and greater complexity. Yet in some regions, that development never came to pass, and marcher lords had their ambitions crushed generation after generation. Indeed, ambition was a primary motivation for Sangheili clans to leave their hearths and halls and settle the frontiers as marcher lords. While they may initially struggle, their descendants would one day reap the rewards and prosper, while singing praise of their ancestors and their glorious campaigns to pacify the march.

This was especially true during the Covenant's Late Antiquity and early Feudal Periods, when the High Council launched sweeping territorial expansion initiatives and handsomely rewarded clans for settling the march. Reforms such as the Mandate of the Sixty-Three ensured that the marcher lords would have unprecedented power over their new territories, along with generous exemptions from High Charity's tithes. Beyond securing and civilizing the marches, no further military service was mandated of them for generations. As High Charity's ecclesiarchy would later come to realize, this had several drawbacks. First, it vastly inflated the Sangheili aristocracy, whose proportion relative to the commoners had been in a steady upward climb since the incorporation of the Unggoy. Second, it made the marcher lords haughty, and distanced them from High Charity as the generations passed. Even as the holy city toured some of these worlds and rewarded them for their loyalty, for countless marcher lords High Charity's light was but a dim memory - for the Holy Ecumene was vast, and there was only one High Charity.

And so began sedition and the rise of radical ideas. Many marcher lords had grown powerful and wealthy with bounty and plunder from their conquests, and so they began to entertain the thought that perhaps they did not need High Charity anymore. Many had religious ideas that conflicted with the Covenant mainstream, and instated reformations or crusades without High Charity's permission. Some secretly hoarded holy relics to themselves, or sponsored unsanctioned research. The marcher lords fought each other, they fought the High Charity loyalists, and they fought the armadas of the holy city itself. This was the Long Discord, and it was ended only by ages of High Charity gathering back its power, culminating in the cascade of reforms and campaigns of reconquest that was the Second Illumination. Rewards and remissions once given to marcher lords were gradually scaled back over the centuries. By the middle and late Consolidation Period, being sent to patrol the peripheries was seen more often as a punitive measure than an opportunity for a Sangheili commander. Where mighty lords had once led great expeditions out into the unknown, such duties were now given increasingly for Kig-Yar privateers under the watchful eye of the Ministry of Tranquility.

Following the Human-Covenant War, the Human Sphere is regarded by many ex-Covenant as being part of the march, with humanity discussed variously either as a Fringe or Ulteria species, though some have argued that such distinctions hold no meaning anymore or should be reexamined.

World types[edit | edit source]

Hub worlds/Focals[edit | edit source]

While the Urs system and the Sunlit Worlds surrounding it are often spoken of as the Covenant's center outside High Charity, strictly speaking the Covenant hasn't had a single core for at least two millennia. There are over two dozen distinct centers of activity across the Holy Ecumene that can stake a claim to that title, a development partly borne out of the Covenant's power structure and the increasing importance of its mobile capital. The Covenant's vast fleets and lesser mobile city-stations that moved across the empire only accentuated this development. There was always something going on somewhere, and for the most part these centers of activity - themselves encompassing dozens of worlds - went about their own affairs.

Covenant hub systems are more than just highly populated worlds. They are the dynamos of the Covenant civilization outside High Charity, home to considerable wealth, power, as well as industrial and military might. Many Covenant prime worlds are ringed with orbital infrastructure and habitats numbering in the thousands. Even on their own, such systems (coupled with the neighboring tributaries that were usually placed in their vassalage) would be capable of challenging a lesser interstellar polity. After a point, the wealth and prosperity of even the most ancient and powerful worlds tended to plateau, and it was new, untapped resources and Forerunner relics that brought wealth and prosperity to worlds. The mobile capital and the consequent constant mobility of goods and people across the empire curtailed the overall importance of any regional hub world, and kept their influence largely confined to their respective parts of the Holy Ecumene. This was also one of the ways High Charity maintained its singular status, ensuring no major world became too powerful.

- Cathedrae

Also known as synod-worlds, these are the capitals of primary domains. These are usually foci of commerce and/or culture in the confluence of slipspace routes from which colony-clusters spring. Usually have multi-species populations in the billions; while their exact species makeups vary by region (e.g. Yanme'e are far more prominently represented in the Covenant's galactic trailing side), they often form microcosms of the Covenant hierarchy as a whole. Most such worlds are surrounded by habitats and industries, as well as orbital farms and various other infrastructure.

- Cradle worlds

Due to the Covenant's immense age and the mobile nature of their capital and many other worldships, species homeworlds are not always as important on the whole as one might think, though this depends on historical factors as well as the species' general perception of the homeworld. The most notable homeworld by far is Sanghelios and by extension the Urs system, though many ancient Sangheili and/or Covenant colonies rival it in power.

- Bastion-worlds

Hub worlds with a particular focus on military assets are sometimes known as base worlds, or bastion-worlds; most hub worlds begin this way, or as lesser outposts.

- Reliquaries and shrineworlds

Worlds largely noted for their wealth of Forerunner artifacts. Usually overlaps with bastion-worlds and/or cathedrae, as wealth, interest and attention and thus Covenant civilization usually cluster around Forerunner artifacts. A world would typically only be explicitly classified as a reliquary if the relics there were of major importance, or the main reason for that world's settlement.

Tributaries[edit | edit source]

Even during the Covenant's reign, poorer, isolated worlds with only limited contact with civilizational hubs, could easily regress in their technological capabilities, fully or partially; some worlds only had advanced tech where it pertained to the produce they contributed to the Covenant in the form of tithes (which could be e.g. troops or foodstuffs), while most of the populace practically lived in a near-medieval state, and higher technologies standard on major hub worlds or High Charity were regarded as exotic luxuries available only to the higher aristocracy. This was just as often due to the Covenant's draconian technological hegemony, and the complexities of how that technology trickled down (or failed to trickle down) the Covenant hierarchy and to less trafficked corners of the empire. In the case of worlds that primarily contributed troops for the Covenant, this was even desirable, as harsher conditions were considered to produce fiercer warriors. Many Sangheili in the Storm corps in particular came from such worlds; while they were regarded as less sophisticated and ill-suited for command roles, at least in the first years of their service, they made for excellent shock troops known for their brutality.

- Freeholds

Worlds held by lesser species, usually Unggoy or Kig-Yar, not in serfdom to any Sangheili lordship. Often had such technological restrictions imposed on them intentionally so as to prevent them from becoming too powerful and challenging the ruling classes.

- Fiefs and Thrall-worlds

Worlds whose primary population consists of lower-caste individuals existing in direct serfdom to usually Sangheili lordships, though some Yanme'e hives also maintained fiefs, particularly on the Covenant's antispinward side.

- Swarmworlds and hive-worlds

Worlds given over for independent colonization by Lekgolo and Yanme'e, respectively. These tend to enjoy more freedoms and less direct supervision than normal fiefs or even freeholds at times, though they are usually tied to local Sangheili states nonetheless. Lekgolo swarmworlds are usually otherwise barren worlds suited to the Lekgolo's extremophilic nature. The Yanme'e typically prefer to inhabit low-gravity worlds or even artificial habitats with large sections maintained in close to microgravity.

Worldships and space habitats[edit | edit source]

A large number of Covenant citizens do not live at the bottom of gravity wells. There are systems where transit nodes do not house habitable planets and stations are built there instead, becoming major centers of population and commerce. Templates exist for such stations, but just as many are custom-built for just that purpose. As well, most decently inhabited systems feature dozens or hundreds of habitats in addition to their primary worlds.

Peripheral worlds and Outliers[edit | edit source]

Not all worlds within the Covenant's cultural sphere were under the direct influence of High Charity and its provincial institutions. These peripheral worlds did not contribute meaningfully to the Covenant and functionally existed outside the hierarchy. Rogue colonies were often established on the part of dissidents or dishonored leaders unwilling to face civil society again, but also self-entitled messiahs, demagogues and ideologues seeking to establish their private utopias outside the High Council's reach, usually accompanied by sizable populations simply looking for a better life in times of unrest. Usually, such rogue civilizations either withered away quietly, fell to internal conflict and/or descended to barbarism, only to have their remnants later brought back to the fold. But in select cases this did not happen, and offshoot civilizations that had escaped the Covenant's notice (likely due to incompetent and/or internally troubled administrations at the time) managed to develop on their own for centuries and flourish. Covenant history records several reintegration wars being borne of such cases, and no one knows how many rogue fleets simply escaped beyond the Covenant's reach. And now, with the Great Schism, it is impossible to predict how extant splinter civilizations might play a part in the interstellar politics of the coming millennium.

Uninhabited worlds[edit | edit source]

Charted worlds without habitation for one reason or the other, ranging from unspoiled paradises to barren airless moons and various types of deathworlds with native conditions too extreme for most species. These make up the majority of the worlds within the Covenant sphere.

Forbidden worlds[edit | edit source]

Worlds where landing is forbidden except by express permission; this may be for many reasons, such as keeping the world pristine, dangerous ancient technology, or some form of cover-up.

Communications[edit | edit source]

Covenant superluminal communications networks are set up largely in tandem with their administrative hierarchy. There is an empire-wide network, used near-exclusively for high-level political and military communication. The physical infrastructure that enabled this network was firmly within the realm of entrusted technology due to its strategic implications, and the very creation of this network during the Second Illumination precipitated a major change in the domains' political makeup. This high-level network was exclusive to domain authorities, and required ministerial priest-technicians to maintain.

The current empire-wide communications network largely follows the structure of the Arterial Network, linking the domain hub worlds. This was instated in the wake of the Second Illumination, when High Charity reconsolidated power under itself following sweeping territorial reforms. In order to maintain good relations with the regional dioceses and the secular polities under their care, the High Council issued an edict for the reorganization, standardization and partial recreation of the Covenant's imperial communications network and its protocols, which were rebuilt according to the structure of the new domains. In theory, each primary domain was to have a central superluminal communications hub (usually in a system of superior slipstream coverage, which was usually also near or in that domain's main religious center). The primary domain hub would possess a high-power wavecaster, which could transmit information to and from High Charity virtually regardless of its location at the time. Lesser domains, in turn, would have their own regional hubs that connected to the primary domain hubs, though wealthier and more powerful lesser domains could occasionally be fitted with communicators capable of contacting High Charity directly even if the holy city was kilolights away. Individual worlds or systems would usually have their communicators linked to local networks with signals routed through the lesser domain hubs to the primary domain ones, though with the sheer volume of data traffic being transmitted across the Covenant, direct channels to High Charity or even further-out primary domains were almost invariably reserved for key governmental or military communiques. That said, this described the ideal outlined in the initial stages of the program. Because of the extent of the Covenant and the bureaucracy of its administration, the changes took centuries to take effect and certain areas were never brought under the coverage of the new system.

This system was complemented by a vast array of secondary means of communication, including ship-to-ship information-transfer protocols among Ministry fleets, merchant organizations and commercial guilds, military or religious orders, and finally individual spacers. Although high-end FTL communicators were exclusive to the Ministries, at least in theory, less effective and often localized means were available commercially, and it were such systems that formed the backbone of day-to-day communications networks in most lesser domains or worlds.